‘So I’m no chef,’ Nick Friedman of Jamon Jamon tells us after we ask him how it all began. A bold statement from the founder of Jamon Jamon and Deluxe Dogs, a Portobello Market stall operator of 18 years and an irrefutable festival connoisseur.

Yet not a completely unsurprising one after you spend time talking to him. Nick’s journey to founding his business didn’t necessarily originate from a love for cooking that needed to be shared with the world. Yet, his passion for what he does is palpable, so when one listens to the organic journey that led to him founding Jamon Jamon and turning it into the success that it is now, you begin to understand why he would make such a surprising assertion.

When ‘no chef’ Nick came to London from South Africa, he had ‘never really cooked much.’ Nevertheless, as an immigrant in a new country, Nick was poking his finger into many different pies (pun very much intended). ‘I think it comes with being an immigrant. It’s never enough to do just one job.’

And so he didn’t; working in tech during the week and hustling delicious imported Spanish meats online at the weekend, Nick had his sights set on retiring and living the life of Riley within three years. ‘Fast forward three months later, I’d sold five portions through my terrible website, two of which were to friends of mine and I was broke sitting there with a few hundred quids worth of vacuum packed ham and cheese in the fridge, thinking that this retirement thing was not going to work out.’

So how did Nick go from an expensive inventory of Spanish ham and cheese getting cosy in his fridge, to his fourth year in a row booking Christmas at Kew Gardens? Simple; incredibly hard work, imaginative thinking and genuine enthusiasm. ‘A friend of mine said ‘why don’t you try the street market, selling ham and cheese baguettes?’ and so I went and got a stall, picked up my Spanish friend and stayed up through the night making 20 Spanish omelettes.’

Those Spanish omelettes, the successor to ham and cheese baguettes, soon became chorizo rolls before finally settling on paella after, as Nick himself says, ‘just generally cooking and buying bits and pieces of equipment and generally figuring it out.’ You would be forgiven for thinking that Nick’s journey was simple.

He tells his story in such an honest, open and seemingly obvious way, one could almost believe it easy to replicate. But what sets Nick apart is his love for what he does, driving him to seek out what makes him happy and in turn better his business.

‘I wasn’t making crazy money in my day job, so [the stall] was a nice supplement to it but I wasn’t that bothered by the money. I think I was more enjoying the dopamine hits of engaging with customers and the other traders.’

A joy for engaging with customers is a golden thread that runs through Nick’s narrative and it is clear to see how this, coupled with a great sense of community with other street food traders, is a notable factor in why he has stuck it out for so long. ‘I’ve always aimed for the best value, which means I want you to buy it, enjoy it and go ‘you know what? I’m happy with what I paid and happy with the food.’’

Ensuring that customers are happy with their food is often easier said than done, but the authenticity of Nick’s paella undoubtedly helps. So much so that in an article disparaging the quality of paella outside of Spain, he was listed as one of the few places where you could get decent grub.

‘There was a very well-known Spanish blogger lamenting the paella that people were buying in supermarkets and how drab and soulless it was. Then in the bottom paragraph she listed two places in the UK that actually save paella for Spain. One of them was mine.’

Small wonder then that such a compliment had Nick racing through the airport to show his partner the article, forgetting that it was entirely in Spanish and she couldn’t read it! Authenticity is arguably a hard line to tow when you’re ‘a South African kid making Spanish food in London.’

It can be hard to balance staying true to a dishes’ tradition, whilst adapting to the realities of serving food on a much larger scale at a market in cold, rainy England. ‘It took me five or six years to learn about reheating our paellas after they’d gone cold, especially in the winter. A member of my staff said ‘why don’t we reheat it?’ and I said ‘no you can’t do that, they don’t do that in Spain.’ He was Spanish and he said ‘but Nick, we’re not in Spain.’’

This lightbulb moment is a lesson that Nick admits he wishes he had learnt sooner. ‘We didn’t throw away food very regularly, but it was a lost opportunity to make some more money. I was thinking about every time I’d been in Spain, I’d never seen anyone reheating paella, but of course not! It’s like 55 degrees there, of course they don’t reheat it! But we’re producing on an industrial scale, we’re not doing what they do in Spain. We’re doing what we do in London, where it’s 4 degrees in January.’

But there are things that Nick won’t compromise on, regardless of the unpredictable British weather. ‘We use the same ingredients that they use in Spain. I won’t compromise on that. We use a good quality stock, we don’t use food colouring and we use saffron. So I think it’s as authentic as authentic can be without us being in Valencia using rabbit, or wood, or water, from the local village.’

Unquestionably a significant learning curve for Nick, it proved to be one that came with a two prong solution. Not only did this adaptation increase profits, it also greatly reduced his waste. ‘If I had thought more about how to waste less stuff, then that would have saved an enormous amount of money. But it’s not just money, it’s the ethical impact of it all.’

During a trip to Vietnam in 2012, Nick visited a rice paddy and was faced with the visual indicator of how much food he had been wasting. ‘I was watching these guys work there and realised that in one year, I had thrown away 50 people’s work and I thought, I need to do something about this. I know it wasn’t me personally affecting them, but all of that stuff had been grown just to be thrown away and I didn’t want to do that food chain of destruction anymore.’

Whilst conversations around environmentalism and sustainability are growing in popularity, subsequently increasingly a global consciousness as to how our decisions impact the planet, it is worth noting that Nick was well ahead of the curve with this thinking. Environmentalism has been of great importance since time immemorial and many businesses have been making concerted efforts to improve their environmental impact.

Nevertheless, rewind the tape to 10 years ago and we have Nick making a conscious decision to waste less and improve the environmental ethics of his business, resulting in approximately 90% of his waste being either compostable or recyclable.

Then again, Nick has never been one to shy away from innovative and imaginative solutions to a problem. Case in point; selling garlic bread at Glastonbury. ‘It was one of those moments where I was thinking how the logistics of paella at a festival just wasn’t going to work.’ But undeterred as always, Nick found a solution. ‘I was looking around and the only snack you could get were chips and I thought ‘I don’t want chips, I want something else.’’

After hearing about a trader who used to sell garlic bread but had retired the year before, Nick thought ‘let me just try garlic bread, why not?!’ And so once he had set up his pitch he got to work, selling thousands of portions of garlic bread. ‘It was great fun, we stick to salamander grills and a griddle and it’s just fun and easy.’ Nick’s ability to not only see the potential for opportunity in a given moment, but also to follow through and give it a try, has now enabled him to go to Glastonbury with his family and ‘forget about the work part of the festival.’

There is something incredibly aspirational about this scope to attend festivals, not out of necessity, but out of choice. ‘I’m very fortunate to be in that position; I don’t necessarily need to go there to make money. My kids still talk about Glastonbury as if they went to the park on the corner, which I think is heart warming for me because it should be fun.’

When Nick began, there was little street food around. ‘We were making paella on the street, banging and clanging and singing and shouting. It was a real destination thing. And then 2009 happened and the street food wave took off. We were right at the beginning of the wave and I’m not ashamed to say I really benefited from that.’ So as someone who has been surfing this wave for some time, naturally one has to ask what advice he would give his younger self.

‘The one piece of advice that I would give everybody, is if you’re going to keep cash at home, make sure that nobody knows where it is. Because when you leave it alone for a week and come back and you find It’s not there, that’s very depressing.’

Emphatically good advice and one that reflects his longstanding experience in the industry. Another nugget of advice, indicative of one who knows every detail of his business, is ‘you need to be in touch with absolutely every aspect of your business.’ ‘Only when you know exactly how to do all your bookkeeping, all of your inputs and outputs etc. should you give it to somebody else to do the admin.’

It is the potential for street food to offer an ‘authentic experience’ that keeps Nick inspired to share his food and as someone who has been at the heart of the growth of street food, you know it holds water when he observes that ‘now you’ve got amazing street food everywhere you go and the stories are great.’

As one listens to Nick share his story, his great sense of enjoyment throughout it all is tangible. The delight with which he shares how an old school fruit and veg trader of 70 years from Golborne Road Market, the first place Nick set up his stall, recognised him as ‘the South African guy,’ casts no doubt on it genuinely being ‘the best thing ever’ for him.

‘I just got really high off those hits of chatting with real life Londoners, serving bankers or serving people who lived around the area. It really felt like I was getting into a different part of London, one that none of my mates could ever dream of seeing.’ His appreciation for Spanish cuisine is one that enables him to be confident in what he produces, whilst recognising that ‘it’s not something comparable to a Spanish grandmother; that’s not what it’s trying to be.’

This confidence in his ability, his business and his food is the result of years of hard work and is undoubtedly reflected in his attitude that ‘if you like it, fantastic; if you don’t like it, also fantastic. I’m still happy.’

You can keep up to date with the Jamon Jamon journey here. For more industry updates and member stories click here.

Featured Training

Featured Training

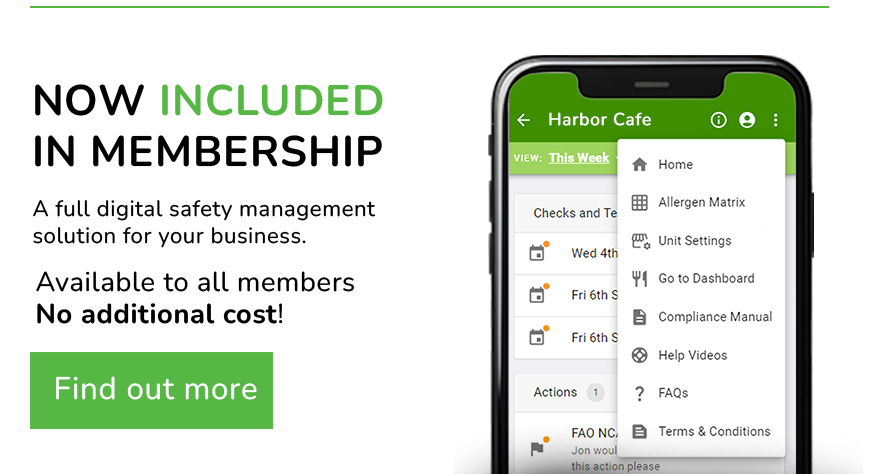

OUR MEMBERSHIP

We're here to help make your catering business a success. Whether that be starting up or getting on top of your compliance and marketing. We're here to help you succeed.

Want our latest content?

Subscribe to our mailing list and get weekly insights, resources and articles for free

Get the emails